Problem-Example-Problem Pairs Trios

I like a good example-problem pair (EPP), when it's appropriate. It's hard to believe that there was once a time in my career I didn't use this structure. It only seems a small tweak from more traditional practice. Think about it, you show students an example and they have a go at some. It's not new. I certainly remember learning maths this way. It's how many textbooks were organised. The 'new' bit, for many people was 2-fold I think. Firstly, having the example and the problem side-by-side on the board/screen. Secondly, that this was not part of the exercise students would complete but more of a check to see if they are ready to practise independently. Traditionally I (and from conversations and blogs I've read, I wasn't alone) went through several examples of the thing I was teaching. Student's copied these down and nodded...I said "yes?", "makes sense?" and "do we understand?" a lot. Which was met with quiet nods or mainly just a lot of silence. Oh and while recalling these memories, I also remember asking a lot of pointless questions. I could be teaching a really complex skill such as solving linear simultaneous equations and if you'd have watched and written down the questions I actually asked students you'd probably have things like "So what's 2 times 3x?" and "24 divided by 3 is?", embarrassing really. But, I digress, that's probably a whole other blog. So rather than a few examples and then let the students do an exercise the example-problem pair framework means you get a much better sense if students were ready to try completing problems on their own. This slight change in modelling examples had a significant impact in lessons. I found students were more engaged in the tasks and needed less individual help. I wasn't faced with a sea of hands as soon as students started to answer the questions. All was good, for a while. However, recently, I found some students and some classes not engaging with them as well as they used to.

Recently, I found some students and some classes not engaging with them as well as they used to.

I also had two trainees this year teaching some of my classes and I could see similar things happening when they used EPPs. It got me wondering about what the issues were and how I could change things. The benefit of observing my trainees was that it made clear to me the aspects of my practice that usually make EPPs work well. I keep an eye on students during the example and ask questions as I go about each part, and how each step follows on. A lot of this is down to experience though. For example, I don't think too much in the moment about the explanation, as I've probably already explained this concept several times over to lots of classes. This means my attention is on the engagement in the room, trying to get a feel for how well they are following. My trainees on the other hand, and rightly so, had their attention split between thinking about the explanation and checking for engagement.

I've heard many strategies for making the most of examples in maths lessons and probably tried most. Things like 'Silent teacher' (described by Craig Barton here) or getting students to have empty hands and watch the board so they are not splitting attention between the example and writing it down. There's also a choice about how students engage with the problem (sometimes called the 'your turn' question). Do they write it in their books or on mini-whiteboards (MWBs). In my opinion it should always be MWBs since why get only a few responses when you can collect responses from the entire class? But I know it's not always practical if it's not common practice in your school.

Anyway, I didn't feel like any of these were going to help with what I suspected to be the issue this time. Students were not engaging with the example enough to transfer the skill to the problem. Despite better questioning, silent teacher, reflecting on each step, more questioning, there were still good students not being as successful as I thought they should when completing your turns or the later task. What I did notice was that they cared a lot more about how to answer the problem. Of course they did. They had to answer it. So I decided to make a small change and start with a problem for them to do instead of the example.

Problem-example-problem trios

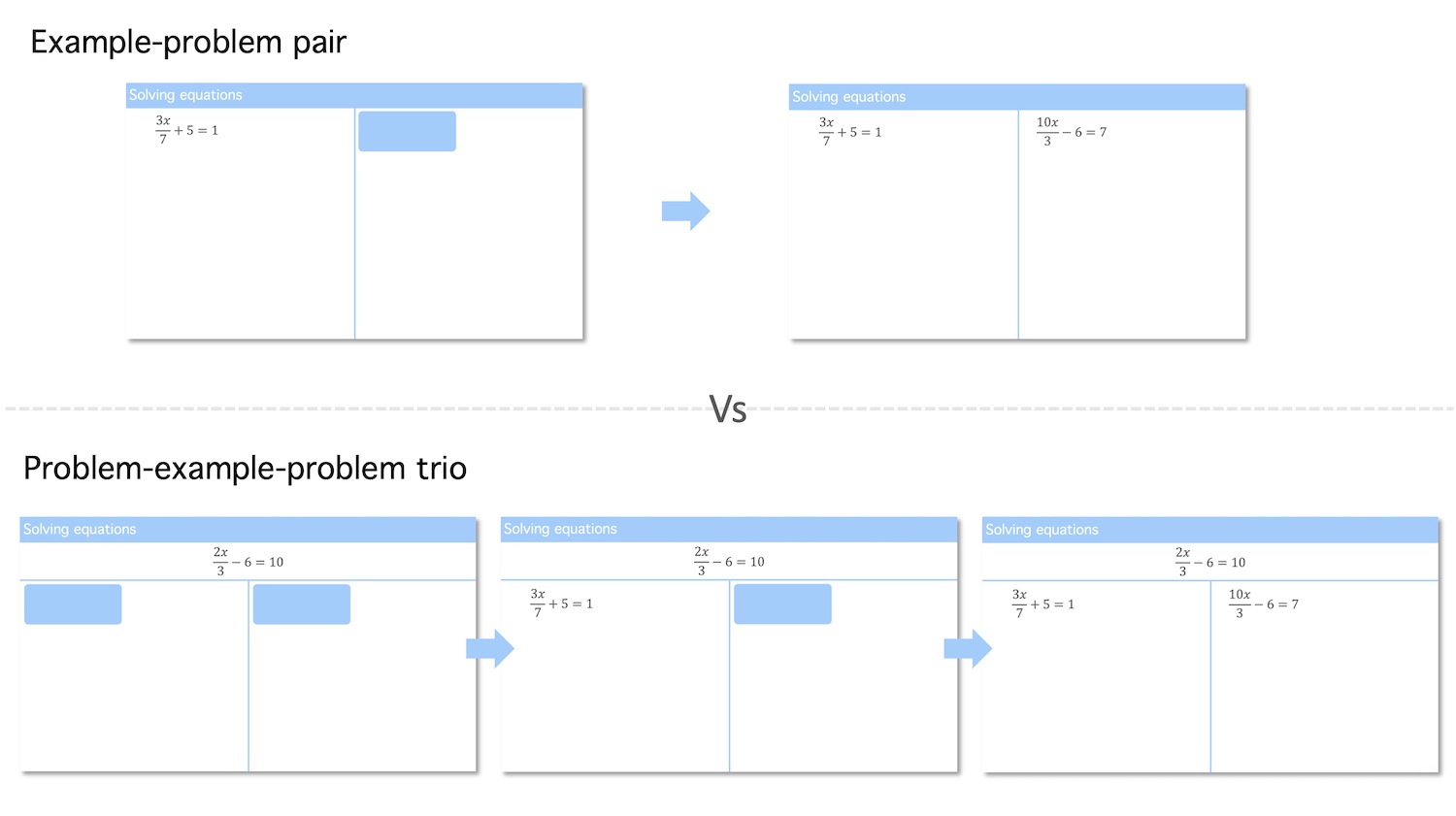

As you can see in the image above, rather than split the board in two and have an example on one side and the problem on the other, which is revealed after the example, instead I split the board in 3 and have a problem first for students to try. This would be done on MWBs and I would circulate the room but not offering help at this stage. Another benefit to this is I can see exactly which part of the skill I really need to focus on during my modelling of the example as I can see where students are less secure. I think context here is key and it's easy to critisise or suggest that there's another problem here but when I'm faced with a situation where the students don't know me that well yet or it's a shared class and the culture is not yet established, getting the students to want to know how to do something by presenting them with a problem first has been something that has worked in these situations. Students like having a go when there's no pressure as I make it clear that it's alright since they might not have been taught this before, or at least for a while. In my classroom, this small change has increased engagement in the example part and increased student success with the problems.

So, I think there might be something in this approach of 'have a go...now I'll help...now you try' but I also think that variety plays a part too. No matter how good a particular technique might be, if we over-use it perhaps it has less of an effect? It's well known a change of pace can re-direct attention or a good story twist or conflict, so perhaps, sometimes, a technique or structure's success could be partly attributed to the novelty of it? Sometimes we feel safe in a structure and perhaps we overuse it. It's only natural. The key is being aware that this might be happening and trying something to see if it could be better.

There are many more aspects of the way worked examples are used in maths that I think are worth investigating in your own classroom, such as the use of thinking prompts, ensuring good questioning, and whether we live model or present completed solutions to students to study. Again, another blog perhaps.

I'd like to finish this blog by making it clear that this structure is ONE small part of a variety of ways I use to explore mathematics with students and how I've tweaked this to be more effective. I see many teachers using the structure in their lessons so if that's you, perhaps this gives you something to reflect on. I'd love to chat more about this so you can find me on mathstodon or twitter.